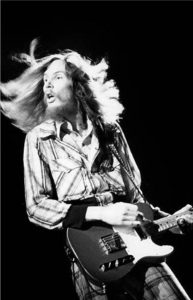

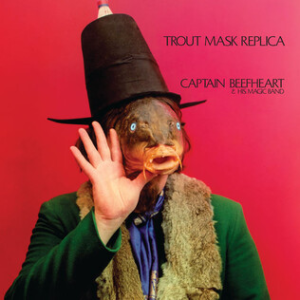

HIT CHANNEL EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: June 2020. We had the great honour to talk with a legendary guitarist: Bill Harkleroad, aka Zoot Horn Rollo. He was a member of Captain Beefheart’s Magic Band, recording several monumental albums with them, such as “Trout Mask Replica”, “Lick My Decals Off, Baby” and “Clear Spot”. He described this period of his life in his autobiography “Lunar Notes: Zoot Horn Rollo’s Captain Beefheart Experience” (1998), co-written with Billy James. In 1974, he formed Mallard with other former Magic Band members. As a solo artist, he has released the excellent “We Saw a Bozo Under the Sea” (2001) and “The Mask Tracks” EP (2014). He was ranked #62 in a Rolling Stone magazine list of “the 100 greatest guitarists of all time”. Read below the very interesting things he told us:

What are the current projects you are involved with?

What are the current projects you are involved with?

Basically, the only thing that I am involved with is teaching. Of course, I ’ve been teaching online for 7 years in total and in the current situation it seems that nobody is interested in performing and I stop touring quite a long time ago. So, basically, I turned my life around, as I ’ve been an online guitar teacher, although I practice three hours every day and I have projects on.

How did you come up with the idea to do “The Mask Tracks” in 2014 inspired by masks created by Roger Evers?

I’ve known Roger for 40 years, probably. He is a poet, writer, painter, sculptor and he did these masks. I went to his art studio and saw the masks. I thought I liked the masks, there were inspiring, but I like the idea of having something besides just what I have learned musically with its own vocabulary. I like the idea of having something to unify what I did and I thought: “OK. Let’s do something that has no boundaries and I could just go on with the image of the masks and see if I would create music for this”. I have always liked to do some film or arts, because it’s always much harder as you play something that you are told to play rather than what you normally play with your normal vocabulary. So, using masks as a source to make a piece is appealing. Also, I have a mask that I am staring at right now in my room. I was never able to do that mask justice.

Is there any concept behind your solo album “We Saw a Bozo Under the Sea” (2001)?

Yes, the same thing. That one involved people. “Elvis Beans” was a self-portrait, because of “Big Eyed Beans From Venus” and there was a connection to that and me and I was born on Elvis Presley’s birthday (ed: 8 January). “Dancin’ With the Doorknob”: When I was kid, my sister was dancing. She was dancing with the door and then she made me dance with her, pulling me all around, when I was 5 or 6 years old. “Still Living With Mom” is pretty obvious. So, basically they are all people. “Don’s Secret” is about Don Van Vliet (ed: Captain Beefheart). They are all just portraits of people. So, that’s what I tried to use as an inspiration again: I was playing what I liked, having been inspired by some people that are important, at least to me.

How emotional was it for you to write your “Lunar Notes” autobiography?

How emotional was it for you to write your “Lunar Notes” autobiography?

Very and I think I stated it accurately, we are talking about a long time ago. My sister and father and two of my very best friends, had just passed away in a very short period of time. When Billy (ed: James, co-writer of “Lunar Notes”) approached me about the idea of doing it, I thought it was a great time to have a cathartic experience, to just rid myself of the Beefheart drama. It just seemed that it was hard; it was a big hit for me to lose both my father and my sister in a very short period of time. She was quite young. I just thought: “OK, let’s just talk about this”. In fact, the first half of the book was difficult for me. Basically, I just stopped as I wrote the first third. I didn’t want to answer questions anymore, because it was going to a place that it wasn’t really me. For that part of the book, I needed to keep in mind the people who were gonna pay for the book, so I had to write a lot about the Beefheart stuff and I didn’t want to be too negative. I was trying to be realistic about what it all was. For me, it was just a cathartic experience. It was: “OK, that’s what happened. Now, I’m moving on”.

When you recorded “Trout Mask Replica” (1969) did you realized that you created one of the greatest albums of all time?

(Laughs) That’s been said a lot, but I ‘m not gonna say that it’s one of the greatest albums of all time. It’s just because I am too close to it to speak about that. No, I was 19. I knew that he (ed: Don) was trying to be an abstract artist and I was aware of his creativity and the full package of the very rehearsed sonic mayhem and the poetry. I was into it. We were in the process of practicing something like that. It starts really changing you and growing on you. No, I didn’t realize that 50 years later I would be still talking about it. But should I? The short answer for you is: “No, I didn’t realize that it would have the impact that eventually has”. I guess I’m lucky that I’m inside it, because some old man can work on line and teach. I’ve been playing my whole life. But it’s a good thing, you know. The fact is that I closed the door on all these things a long time ago, so that I can do my own thing.

How challenging was it for you to decipher Don’s ideas on “Lick my Decals Off, Baby”(1970) album?

It’s a good question. I have to really think about it. Hard task, when somebody is using a piano to express something, but he really doesn’t play piano. I didn’t notate anything. I listened to something, and if I needed to, I ‘d have him to stop, so I could make some notes on what was played. Just listening to a cassette and listening to him pounding away, was hard to decipher. I wasn’t doing notation. Those parts were really hard. In songs like “Peon” and “One Red Rose”, I moved parts around. I didn’t really change anything, hardly at all, one thing here and there, but I changed the order of things to make them more reasonable. When I played them back to him, he thought they were wonderful songs. He obviously didn’t know what order they were arranged whatsoever. Those parts were actually easier because he was playing on the white keys (laughs). So, there’s C major/A minor and if you notice, he played things with black keys which are a pentatonic scale E-flat minor and G-flat major and he was separating white keys and black keys unlike “Trout Mask Replica”. I like those two solos parts, they are pretty good to hear.

Would you like to tell us a few words about your guitar playing on “Big Eyed Beans From Venus” from “Clear Spot” (1972) album?

Would you like to tell us a few words about your guitar playing on “Big Eyed Beans From Venus” from “Clear Spot” (1972) album?

It’s interesting, I just answered that the other day. People have a real connection to the tune. Of course, with my name being mentioned, it makes it to stick out as well as the slide part I did on that. But basically, it was a very typical thing for us to play and a lot of other people to play. When you use the drop D tuning, which is just dropping the sixth string of the guitar to D, rather than the E, it is very connected to the Irish sea shanties. It’s not a style that I like. I don’t really like fingerstyle, but it was something that we did a lot. So, the rhythm was more a Delta Blues rhythm, but the parts of the song were very-very simple. It was a very simple tune, I think.

In your opinion, what made Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band so unique?

That’s an easy answer: Don Van Vliet. He was an extremely intelligent and extremely creative person, but I think when he was younger he was just prone to his inability to be with other people very well. I think he probably could have been diagnosed with something, whether it would be any number of things: Bipolar, Asperger’s, whatever symptoms that are displayed by people who are diagnosed with these disorders. I’m pretty sure that if he wasn’t in that band in ‘69 or even before I was in the band and he was around now, his career would be over. The problem was that he wasn’t diagnosed. That created a real dynamic person with intelligence and creativity but also with this other not that fine side of him. Personally, if I had met the other guys: John French (ed: “Drumbo” -drums), Mark Boston (ed: “Rockette Morton” -bass) and Art Tripp (ed: “Ed Marimba” -percussion), we would have a blues band. So, all the creativity that made the music to stand the test of time and to stand all that, it’s truly his creative force.

“The Spotlight Kid” and “Clear Spot” have a more mainstream sound than “Trout Mask Replica” and “Lick My Decals Off, Baby” albums. Was it intentional or it just happened?

Yes, it was intentional. He gradually changed different members of the band. I can’t remember how many changes they were. Fifteen? I can’t remember. But there were people who were in the band for three months; they couldn’t tolerate him. I won’t say as much as the “Clear Spot” because “Clear Spot” was a nice transitional version between the early R’n’B, blues-based stuff that showed the Beefheart edge. In fact, when “Clear Spot” was being done, he was kept in check by Ted Templeman (ed: Van Halen, The Doobie Brothers) -the producer of the album- out of the studio area. He was keeping him away for us, so that we can do our job without his craziness. Don on “The Spotlight Kid”, he was slowing things down because “Trout Mask Replica” and “Lick My Decals Off” were too fast for him to sing. It was his fault to move away from -in my opinion- a more creative version of the band. I think “Clear Spot” is in a good medium place. I don’t like the “Spotlight Kid”. It’s obvious in all my interviews, although there is one or two tunes, that are OK. And then the last album (ed: “Unconditionally Guaranteed” -1974). It was just a band that it didn’t want to play for Don. It was done and we all thought that it was time to go, because we needed money. We were poor. It was a OK thing, but musically I wasn’t happy with the direction.

Do you still believe that you were brainwashed by Don Van Vliet? You said that in an interview, that he went to the library reading books on how to brainwash people.

Yes, I did. How long ago was the interview? (laughs) You’ve got to remember all the time what you ‘ve said for 50 years. So, my reaction in answers, through memory loss, through me growing up as an adult, could be different. I know I said this thing in magazine interviews, right after we broke up, when we went out and we were doing Mallard. I bet there were a couple of things that I probably shouldn’t have said, that they were real and right. But, I don’t like the fact that I said those things in public.

It was in a 1999 interview in University of Oregon Voice.

It was in a 1999 interview in University of Oregon Voice.

Yeah, I know the interview you are talking about, because I knew the journalist. He was a student of mine. But yes, he apparently did that. I was told that I think by John French, that he went to the library and he was very prone to sleep deprivation and using people against each other to create and control. So, he was very much aware of that. He could do anything. It’s not the same, but I think Frank (ed: Zappa) in a way, did that with his group, not as intentionally as Don did. He did it fοr a long time before, and I had just come out of a hippie cult and I was pretty easy to be pushed around. Yes, I was, in actual fact, and that’s how I took it, because I was a very beat-up person that was so afraid of dying in Vietnam and I didn’t know what to do with my life. Then, I ended up in this band, my absolutely favourite band. It made me an easy target and I put up with more bullshit than a normal person would do.

Did you get on well with Frank Zappa?

I always did. He was always very nice to me. He showed me things. You know, he showed me some music things, guitar things. It’s quite obvious that when he was actually in jail, for a few months, he created all these cool tunings. I wish I had the cards he wrote. They were 3X5 little cards that he had written on scales and things and showed me those. Every time we had any conversation and any interaction I had with him, it was always positive. He was always busy, he had an edge to him, but he never delivered that to me.

Is it true that Don consider his music better than Frank Zappa’s?

I can’t speak to that, really. I could say that he tried. But he said a lot of things and he contradicted himself 10 minutes later. Of course, he said that what he did was better than everything on the planet. He also said that he wrote every single note and he didn’t even know what the notes were. Sometimes we would, but whatever he said you can’t buy it, because it’s too bullshit.

Did you enjoy the US tour with Jethro Tull in April 1972?

Did you enjoy the US tour with Jethro Tull in April 1972?

(Mad laughs) I’m sorry, your question is fine, but you are asking me for a thing so far back, I’m 71 years old. In fact, I don’t remember yesterday. I can’t speak about that particular tour. When we worked with them, whenever that was, it was an easier job. We were the opening act. It was easier to do a shorter set and get off the stage. We were taken care better because of the size and the enormity of Jethro Tull. Also, we had more interaction with them than other people, so it was more comfortable for us. Our band was probably the best solid unit at that point, when Mark Boston was on bass, I was on guitar and John French on drums, percussion etc. To answer you question, yes, I think I enjoyed the tour, but touring was never that fun for me, so I stopped doing it.

What made your to form Mallard?

Not knowing to do after leaving the band. Being only a musician and having no job skills, I always loved music, I still do. I practice three hours every day. Mark Boston’s impetus was huge. He really wanted to do that. He liked touring, he wanted to be seen; I didn’t give a shit about it, I wanted a job and touring wasn’t as much fun. Mark still had a contact with Ian Anderson and he was the impetuous force to create that. Right after we quit (ed: Captain Beefheart), we kind of fell apart. We didn’t know what to do. Mark kept in touch with Ian. This was only in a matter of few months, but to me, when I was that young, a few months is a long time. That’s the way we formed the band and tried to just keep it going, Ian helped us out with that. He really helped us to do that and that’s why I did the two albums with them.

Is it flattering that Ian Anderson is an admirer of your talent? He called you “the most musically organized of the guys”.

Oh, he did?! Oh, thanks, Ian. I haven’t talked to Ian in years, but thank you. He was always very nice to me. He just disappeared but of course he was a very busy man. That’s very nice of him. It’s always flattering. I feel, whether is a fan or somebody who is enormously famous like him, it’s wonderful to hear. Hi, Ian! I don’t really think about it that much. I just do what I do and if in that process, somebody enjoys it or it affects his life in some positive way, lucky me!

Why did you destroy the Mallard sessions featuring Ian Anderson? I read this on Wikipedia, in the article on Mallard.

No, it’s not true. I didn’t destroy anything. I didn’t have access to anything. I actually have an acetate disc, which is the pre-vinyl when you make a record. It features a tune Ian wrote and has Mark singing. I have that in my basement as something that happened during those sessions, but there is no way I would have my hand on master tapes or anything like that. In fact, I can’t imagine destroying anything like that.

Were you surprised when Rolling Stone magazine put you on #62 of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time in 2003?

Were you surprised when Rolling Stone magazine put you on #62 of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time in 2003?

I was very surprised, mainly because when you look at the list, with a few exceptions -there are some old guitar players, they are dead for a long time now-, all those people are much more famous than me. I think it was more a popularity list rather than a guitar skill list, honestly, because as far as the list itself, it’s ridiculous (laughs). All the great guitarists that I know, they are not on the list. It’s just the rock side of the guitarists, and the list was not accurate for that. I’m flattered, to use your term, that I ‘m on that list, mainly because my name is still out there, while I wasn’t out performing and being out there like everybody else on that list. So, that’s a compliment. David Fricke did that, so I will say: “Thank you very much, but some of your other choices are pretty bad”.

Do you have any memory of the Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band concert with Larry Coryell as opening act at Anderson Theatre on 15 January 1972?

Oh, man! You’ve got this thing. We may have played two gigs with him, I can’t remember. I remember the gig and I remember meeting him, because I’m 6’5 and he wasn’t very tall and he played this enormous guitar. So, it made him look like he was a 12-year-old and he always looked pretty young. He looked like a 12-year-old kid when he was playing, I think, with Alphonse Mouzon (ed: drums) and really great players. I remember standing on the side of the stage listening to him. I said: “OK, you guys are great”. Also, we definitely opened for John McLaughlin and Mahavishnu Orchestra, but anyway, yeah, I do remember that. I mean, yes, he was a great player.

Was it an interesting experience to play with Bo Diddley?

Was it an interesting experience to play with Bo Diddley?

(Laughs) I can confirm that. Yeah, I remember that and how it happened. I’ll tell you the story real quick, if I can. I was living in this small beach town in Oregon. They had just opened this small hall and Bo Diddley was hired to play a gig. He comes in, he never had a band, he just used players from the city he played. We were on the stage and he was down on the floor, just looking at it and he told us not to play that beat, the Bo Diddley beat. “Don’t play that”. When he came in, I was playing some slide guitar stuff and we were just jamming on this blues thing and he said: “No slide” and then he started playing a song and we joined in -as he plugged in his guitar obviously- we started playing and he was playing along with us and he said: “Oh, this is gonna be fun. See you later” and that was our rehearsal. Then, as soon as we got on the stage, he told the drummer to play the beat, he told me to play a slide solo, which I wasn’t ready for because he told me I wasn’t going to. It was all for him. I know what it was: It seems like he was used to play with probably some marginal players and in this situation, he could tell right away that we could play and he let us go, but also it’s a bit of control on his part. As if he was saying: “You’ve got to watch me. Then, the gig was two hours long and it was very good. He got our shit together. I was kind of blown away. He enjoyed it because again he could play freely.

How important was the influence of John Coltrane on you?

As much as anything. I would say Coltrane happened first for me, in that bunch of people. I was listening to jazz and learning to play jazz when I was 14, but not very aggressively. I didn’t really like the standards that he did a long time before. They sounded so old-fashioned to me, but as soon as I started really listening to his albums like “A Love Supreme”, I realized that nothing can get any better than that. I liked Miles Davis but I ‘ll keep him (ed: Coltrane) always in a perfect place, mainly because I was very young and I wanted to hear more notes. As I aged, I realized how good Miles Davis was, because he played silence better than anybody. The next generation of that for me, was an enormous influence on me, after all the Beefheart stuff, was Michael Brecker. I saw him as extension of the Coltrane thing and now Chris Potter.

There is a nice story about Muddy Waters in your book. Would you like to share it with us?

With Muddy? Yeah, I think I remember that. It was the first time I met him and I think I had been in the band maybe a week or two. I met Harry Partch and Muddy Waters within the same two weeks since I had joined the band. We watched Muddy Waters at Shelly’s Manne-Hole in LA, when he was playing. Muddy came up to the table and that: “I’m not gonna be good tonight” or something along the lines of “I got a cold”. He kind of made an excuse and I thought: “This is Muddy Waters”. Then, they went to play and I didn’t even know if I was hearing him because I was so blown away then. I’m 19 and here are all these people: Harry Partch, Frank Zappa, Mick Jagger and Muddy Waters. Pretty cool.

What was like to live in Timothy Leary’s commune?

What was like to live in Timothy Leary’s commune?

I wasn’t in his commune. We were in a sort of an outreach of that (laughs). They were in a commune south of LA and we were north of LA, but we were connected to each other. I think, it was right for the time, for me. It was an LSD cult and it changed my life and it opened me up. I’m glad for what I saw, I stayed too long and it made the transition with Beefheart weird. At that time, I went from one cult to another. It showed how drug stuff had been in my heart, at that young age, that I would be such a victim of people who controlled things. Leary was doing his thing but he was kind of a hippie mafia, really.

Had you ever met John Lennon?

No, I never met John.

A huge “THANK YOU” to Mr. Bill Harkleroad for his time. I should also thank Billy James for his valuable help.

Official Zoot Horn Rollo website: https://www.zoothornrollo.com/